What Do You Like, and Why?

Collectors have their own favorite time periods and specialties, but generally, collectible transistor radios were made between 1954 and 1965, or perhaps the early seventies. (I date myself. Parts of the Internet are all aglow about eighties radios now...)

The first commercial transistor radio, the Regency TR-1 was made in America, and came to market in time for Christmas, 1954, but experimenters were making homebrew sets several years earlier.

The first commercial transistor radio, the Regency TR-1 was made in America, and came to market in time for Christmas, 1954, but experimenters were making homebrew sets several years earlier.

As we age, the “collectible” timeline will creep up, and there are already folks collecting childhood radios from the early eighties. You will find avid collectors in America, Japan, and worldwide. There are many European collectors, and Australians love the hobby as well.

Types of Collectors

I now know lots of wonderful collectors, a few of them first-hand, but many more as the result of Internet correspondence It seems to me that all boomer-aged radio collectors have a few things in common, but they usually fall into perhaps seven different niches. See if you can recognize yourself in one or more of these descriptions. This “self-examination” might help you better-focus, or perhaps broaden your collecting efforts.

Period Collectors

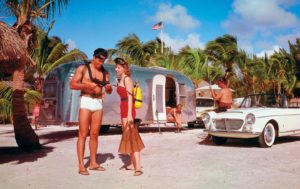

Period enthusiasts are not transistor radio collectors in the traditional sense. They might own a radio or two from their childhoods, but probably also collect mid-century furniture, toys, pop culture posters and so on. They are as in love with the time period as they are with any particular radio, or radio manufacturer or whatever. Period collectors tend to own a few, working, dramatic electronic pieces that fit into a broader household theme.

Period enthusiasts are not transistor radio collectors in the traditional sense. They might own a radio or two from their childhoods, but probably also collect mid-century furniture, toys, pop culture posters and so on. They are as in love with the time period as they are with any particular radio, or radio manufacturer or whatever. Period collectors tend to own a few, working, dramatic electronic pieces that fit into a broader household theme.

Lovers of Vintage Electronics

Mostly, but by no means exclusively men, electronics lovers typically have quite a few transistor radios, but they might also have vintage HAM gear, test equipment, early hi-fi and stereo systems, extensive technical libraries, and perhaps even home-brew projects and collections of unused vintage components.

Mostly, but by no means exclusively men, electronics lovers typically have quite a few transistor radios, but they might also have vintage HAM gear, test equipment, early hi-fi and stereo systems, extensive technical libraries, and perhaps even home-brew projects and collections of unused vintage components.

It’s not unusual to find both tube and transistor gear in their collections, which sometimes spread into both earlier and later decades to embrace old, vintage hearing aids, early computers, electronic pocket calculators, and so on.

Specialists

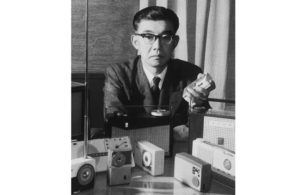

These are, to me, some of the most interesting folk. They pick a particular, very specific niche and nearly obsess over it. Some specialists collect only shirt pocket transistor radios. Others specialize in a particular manufacturer’s sets—Sony or Zenith, for instance. Some want only Japanese radios or just American made sets, or American brands that were made in Japan.

These are, to me, some of the most interesting folk. They pick a particular, very specific niche and nearly obsess over it. Some specialists collect only shirt pocket transistor radios. Others specialize in a particular manufacturer’s sets—Sony or Zenith, for instance. Some want only Japanese radios or just American made sets, or American brands that were made in Japan.

Others become interested in a family of products—Zenith Trans-Oceanic radios for example, be they tube or transistor. There are a number of collectors who specialize in the Regency TR-1.

More than one specialist knows nearly everything there is to know about Raytheon CK-722 transistors, a single component that created an entire hobbyist industry that lasted for decades.

More than one specialist knows nearly everything there is to know about Raytheon CK-722 transistors, a single component that created an entire hobbyist industry that lasted for decades.

There are amateur radio, (HAM) specialists, Novelty radio specialists, crystal set lovers, folks who collect only ephemera—books, schematics, store signs and so on.

A few of these folks use their collections to re-live their professional lives. Since they worked at a particular electronics company—Texas Instruments or Olson Electronics, for example, they have vivid memories of products, projects, coworkers and even their workplaces.

Because of their “insider” status, many have amazing libraries of old sales literature, in-house memoranda and other items of historical value. These folks tend to be our hobby’s unofficial historians, and an important, fascinating part of the collecting community.

Historians

Historians are like Specialists on steroids. They want to gather, catalog and preserve all the details for future generations. Many enjoy publishing their findings, and exhibiting their artifacts. They want to know when the first prototype of a particular set was built, the serial number of the first unit shipped, how many were , which countries imported them, and so on.

Historians catalog the smallest changes in components, circuitry and cabinetry over the lifespan of a product. They want to gather and study advertising pieces, press releases, company correspondence with dealers and all manner of ephemera relating to particular radio or manufacturer. They record aural interviews with people involved in the companies and products they study.

Historians catalog the smallest changes in components, circuitry and cabinetry over the lifespan of a product. They want to gather and study advertising pieces, press releases, company correspondence with dealers and all manner of ephemera relating to particular radio or manufacturer. They record aural interviews with people involved in the companies and products they study.

Sadly, our little sphere of interest (mid-century electronics) has only a handful of true historians, and fewerexhibitions. Even the Smithsonian, which I was told has an amazing collection of boomer-era electronics in its storage area, has very little on display. I haven’t been there in a few years, but during my last visit there was literally one dusty little case with a Regency TR-1 and some other (unmemorable) bits and pieces scattered around it. I have seen better looking high school science projects.

The wonderful private radio and broadcasting museums around the country, (and there are a dozen or more), largely ignore the era as well. This is likely because we boomers are not actively involved with these valuable, almost always non-profit, volunteer organizations.

Until we roll up our sleeves, and put our money and time into helping create displays there won’t be any. So, if you think you might enjoy being a historian, or at least helping one, please drop by your local museum and see what you can do to get our generation’s technology on display. Start by helping our parents and grandparents preserve their artifacts, and help them get interested in our “little plastic radios.” We need more historians!

Restoration Hobbyists

I might be one of these guys. I get a big kick out of making an old piece of electronic gear work again, and enjoy making it look better too. I find it interesting to peek inside and marvel at the variety of technical solutions engineers employed over the years to do everything from pulling in radio waves to moving tuning dial indicators to holding batteries.

I might be one of these guys. I get a big kick out of making an old piece of electronic gear work again, and enjoy making it look better too. I find it interesting to peek inside and marvel at the variety of technical solutions engineers employed over the years to do everything from pulling in radio waves to moving tuning dial indicators to holding batteries.

For us half the fun is found inside the things we collect and disassemble. The other half is making the outside look as close to factory fresh as possible. We restoration nerds typically have more than one workbench, piles of old “parts” sets, smelly chemicals, dirty rags, tools galore, musty service documentation. Squawks and squeals come out of our workshops at all hours of the day and night. It’s a wonder our families put up with us.

Perfectionists

As the name implies, they expect everything to be factory-fresh when they acquire it, something that is harder and harder to achieve now that a lot of boomer-era collectibles are more than fifty-years old.

As the name implies, they expect everything to be factory-fresh when they acquire it, something that is harder and harder to achieve now that a lot of boomer-era collectibles are more than fifty-years old.

I once sold, on eBay, an incredibly rare transistor radio. It went for several thousand dollars less than it should have. This radio was perfect in anybody’s book. Or so I thought.

I went to great pains to pack it carefully and it arrived safely. But instead of my getting a gushing “Wow, thanks for offering this amazing radio” email like those I often get when one of these rare items goes for a song, I got a message from the perfectionist/winner saying in part that “if one looks very carefully under a magnifying glass at the plastic feet on the bottom of the radio, one of the feet appears to be slightly rounded off.” He wasn’t sure if it came like that from the factory or what, and wondered if I knew.

I offered to refund his money, of course, but he knew better than to return such a bargain. He did want me to know, however that it was not a perfect radio…

Perfectionists also usually want unmolested, playing radios containing only original factory parts. This will be more and more difficult to accomplish as the electrolytic capacitors in virtually all mid-century electronic devices will eventually dry out, leaving all collectors with the unfortunate dilemma of keeping our artifacts factory fresh, or replacing parts in order to return them to operating condition at the expense of authenticity.

That’s going to be a really difficult decision for perfectionists. I wonder if it will result in a mini-flood of cosmetically perfect, dead radios for sale on eBay?

Please don’t misunderstand me here. Seeking excellent examples of artifacts is a very important part of collecting. But not everything that rolled off of an assembly line 50-years ago was perfect when it left the loading dock, let alone after years of use and abuse.

Perfection is great when you can find it, but items in excellent and even very good condition can be equally enjoyable for most folks. If you crave perfection, be extra careful when you shop, and ask lots of questions. See comprehensive photos, or better yet hold the item in your hands before you purchase it. And be sure you buy only from sellers with liberal return policies. You need to also face the reality upfront that if your definition of perfect includes working the day will come when nothing in your radio collection will be perfect.

I personally find it fun to discover and wonder about the occasional ding or dent, and a previous owner's Social Secrity number etched on the bottom of a set.

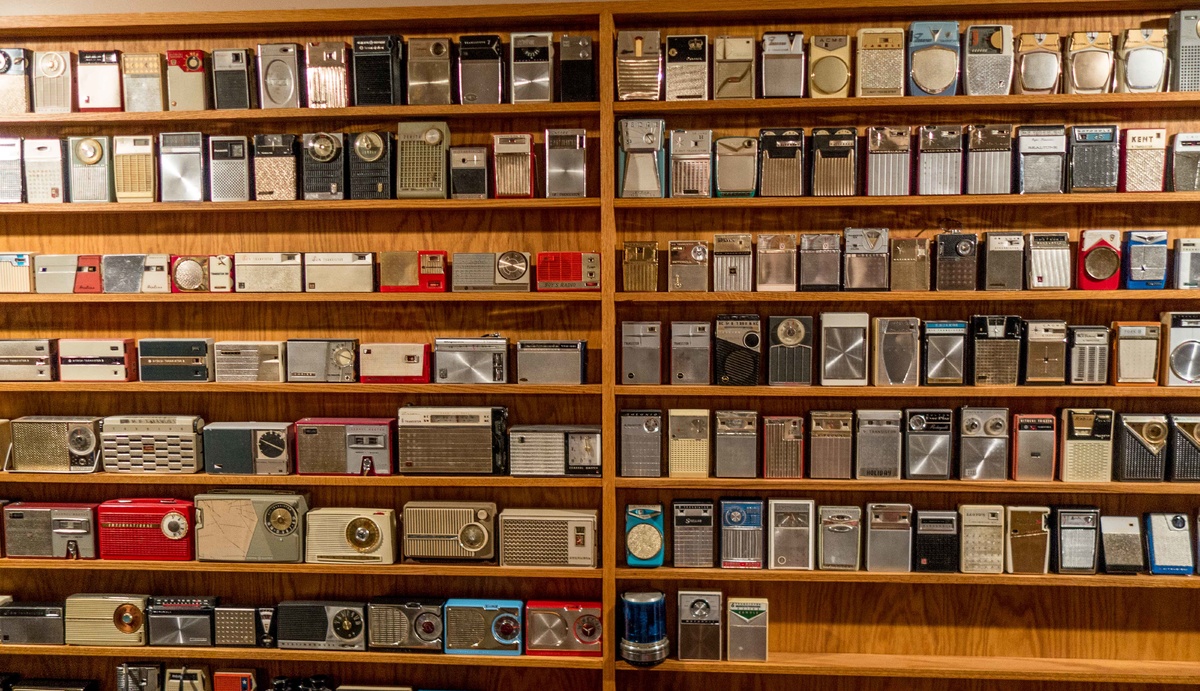

Insatiable Shoppers

You know at least one of these folks. Perhaps you are one. I have been accused of skirting the edges of this lifestyle myself. Sometimes referred to as pack rats, insatiable shoppers acquire and pile, acquire and pile some more. Much of what gets purchased never sees the light of day. It’s squirreled away in bankers’ boxes in the garage, and perhaps in the hallway and in the guest bedroom closet.

You know at least one of these folks. Perhaps you are one. I have been accused of skirting the edges of this lifestyle myself. Sometimes referred to as pack rats, insatiable shoppers acquire and pile, acquire and pile some more. Much of what gets purchased never sees the light of day. It’s squirreled away in bankers’ boxes in the garage, and perhaps in the hallway and in the guest bedroom closet.

Not all pack rats are collectors. I once had the both delightful and depressing experience of walking into a shuttered-up sixties-era radio store that had been owned by a recently deceased shopkeeper. He had locked the door in the mid-sixties leaving behind not only quite a few new-in-the-box radios from the era, but also heaps of abandoned service projects, piles of Heathkit catalogs, manufacturers’ marketing materials, and what appeared to be every nut and bolt and bottle cap he had ever owned in his life. It was now up to his heirs to dispose of what was mostly, but not completely hazardous waste.

It has made me re-think that pile of boxes in my garage. How many “parts radios” does a boomer need? Will we be leaving our survivors a legacy or a nightmarish disposal chore?

What do You Like?

So, again, as we expand our collections, perhaps we should all consider focusing a bit. Here are some questions to ask ourselves. Hobbies ought to be all about discovering what we enjoy and doing more of that and less of something else.

So, again, as we expand our collections, perhaps we should all consider focusing a bit. Here are some questions to ask ourselves. Hobbies ought to be all about discovering what we enjoy and doing more of that and less of something else.

Japanese? American? Fifties? Multi-band? Crystal sets? Two-transistor "Boys Radios? What?

Fix or Just Display Them?

Do you like fixing things, or mostly do you prefer showing them off? And incidentally, just because you don’t know how to repair radios doesn’t mean you can’t learn. That process itself can be fun, and you can leafrn a lot about ig here on this site. So before you say “I don’t know a resistor from a thermometer,” ask yourself if you would like to learn how radios work and how to fix them. You might be surprised at how easy it is and how much added enjoyment the troubleshooting process can provide.

Do you have a place to work?

If you plan to repair and clean vintage electronics give some thought to where you will work. While many boomers are downsizing as their nests empty some of us are turning empty kids’ bedrooms into hobby rooms. The third parking space in a garage can become a nice workshop, especially if insulated, heated and air-conditioned. Learn more HERE.

Many retirement developments such as the ones built by Del Webb and numerous other developers have community centers complete with well-equipped workshops. If you are shopping for new digs keep your hobbies and those of your spouse in mind. Don’t downsize the fun just when you get the time to have some. Also check out the new Worker Spaces popping up everywhere.

Specialize or Generalize?

We have touched on this already. Are you mostly looking for that radio you had as a kid, or wish you could have afforded back then; or would you like to know everything there is to know about radios sold by Sears Roebuck in the sixties?

We have touched on this already. Are you mostly looking for that radio you had as a kid, or wish you could have afforded back then; or would you like to know everything there is to know about radios sold by Sears Roebuck in the sixties?

Would you like to plunk the needle down on an old Beatles LP and bask in the glow of a vintage tube stereo while you polish up an old pocket radio? ‘Wish you had an eight-track player for your vintage Mustang?

How would it feel to talk with astronauts in the space shuttle using a vintage Heathkit transceiver? Just because you don’t have a HAM license doesn’t mean you can’t get one. And no, you don’t need to know Morse code to become an amateur radio operator.

Where Will You Put Them?

This might be the thorniest issue of all. The amount of space you have available for display and safe storage might affect the type of collecting you can do. If you don’t have a lot of space, or if your spouse thinks “those old things look like junk,” you will need to get creative, and perhaps selective.

This might be the thorniest issue of all. The amount of space you have available for display and safe storage might affect the type of collecting you can do. If you don’t have a lot of space, or if your spouse thinks “those old things look like junk,” you will need to get creative, and perhaps selective.

I've written a few tips on how to safely, attractively and compactly store your collection. A good starting tip is to only collect a few really nice items at first rather than a lot of mediocre pieces.

Why Stop?

Why stop with collecting transistor radios when so many other cool things happen in the fifties, sixties and seventies? Test equipment. Vintage HiFi and stereo gear. What else do you collect?

Test equipment

There are two reasons to own vintage test gear. The first is to use it while restoring vintage radios, televisions, HAM rigs and so on.

There are two reasons to own vintage test gear. The first is to use it while restoring vintage radios, televisions, HAM rigs and so on.

The second reason is simply to have a nice collection of vintage test equipment. There is nothing wrong with trying to own every signal generator Heathkit offered, although it would take a lot of room, and probably cost you a bundle. But heck, if you enjoy vintage test equipment collect away. There are even entire books devoted to vintage test equipment. Tube Testers and Classic Test Gear by Alan Douglas is an example. See the Bibliography for details.

Incidentally, I think there’s a middle ground. Some of us own vintage, or near-vintage gear that we use in our daily repair tasks. This, I suppose, is the electronic equivalent of what car collectors call “driver cars.”

In this regard, my preference is for the solid state test gear made in the late sixties and early seventies. It works well, has no tubes to burn out and, to strain the earlier analogy, it still has plenty of miles left on it. To learn more about vintage test equipment check out the third book in this series titled Servicing Transistor Radios.

Audio Gear

Vintage audio can be an addiction all to its own, or can compliment your other artifacts. There was some important innovation going on around us as we grew up. The first transistorized audio gear was sold, and later the first good solid state audio equipment came to market, and so on.

Vintage audio can be an addiction all to its own, or can compliment your other artifacts. There was some important innovation going on around us as we grew up. The first transistorized audio gear was sold, and later the first good solid state audio equipment came to market, and so on.

We witnessed whole new media formats sprout up and wither away. Do you remember eight-tracks? Reel-to-reel tape? Quadraphonic receivers? Early, mono Phillips cassettes? The first Walkman? Microphones from your childhood? The Voice of Music record player in your classroom? The 45-only record player in your bedroom? Of course you do. Now go out and find them again.

Television

“Hey kids! What time is it?”

Well, Howdy, now that you ask, maybe it’s time to think about collecting and restoring vintage television artifacts. You won’t be alone. And folks are rounding up more than just television sets. They are collecting and restoring entire television broadcasting studios, early video recording devices, and programming as well.

Well, Howdy, now that you ask, maybe it’s time to think about collecting and restoring vintage television artifacts. You won’t be alone. And folks are rounding up more than just television sets. They are collecting and restoring entire television broadcasting studios, early video recording devices, and programming as well.

As the first TV generation we owe it to ourselves and to our kids to preserve some of this stuff. It will also give us plenty of fun in the process.

Of course, due to the demise of analog television signals analog sets have nothing to display unless you connect them to Digital-to-analog converters. And then you will probably want to watch shows made in the old 4:3 aspect ratio rather than today's wider 16:9 aspect ratio.

Although my son, a television producer tells me that a lot of 16:9 programming is shot with 4:3 viewers in mind. This is why logos and the other clutter at the bottom of screens are not always at the very edges.

Although my son, a television producer tells me that a lot of 16:9 programming is shot with 4:3 viewers in mind. This is why logos and the other clutter at the bottom of screens are not always at the very edges.

Notice how the Whittier, CA text and the HGTV logo are not near the 16:9 screen edges. Moreover, when scenes are shot the action and important visuals are often kept in the 4:3 area.

So, yes, you can still enjoy watching vintage TVs. You will need an analog-to-digital signal converter--or maybe a Betamax VCR?

Amateur Radio Gear

Did you grow up as a HAM or maybe owned a CB rig and wished you were an amateur operator back then? There’s still time to revisit this exciting era. Much of that vintage mid-century gear is still useful and in use today. Check out GM3WOJ's vintage shack.

Folks are collecting, restoring and using transmitters, receivers and all manner of accessories. Affectionately called boat anchors, much of this stuff pushed the state-of-the-art forward, and is still fun to own and use.

No HAM ticket? Get one. It’s easier now than before and there is plenty of help available both online and in print. Drop by a hamfest or local club meeting to get started. Check the resources directory at the end of the book for places to start.

Vintage Computers

If you are like me, you had a home computer before nearly anyone else you knew at the time. My first was a kit, complete with BASIC programs delivered and shared on cassette tapes. Then I graduated to another kit, and another. By then the two Steves announce the Apple One and I grabbed mine. Wish I had it now! Many of us traded them in for Apple IIs. Rumor is that the trade-ins were bulldozed in a landfill. The survivors are worth a fortune.

If you are like me, you had a home computer before nearly anyone else you knew at the time. My first was a kit, complete with BASIC programs delivered and shared on cassette tapes. Then I graduated to another kit, and another. By then the two Steves announce the Apple One and I grabbed mine. Wish I had it now! Many of us traded them in for Apple IIs. Rumor is that the trade-ins were bulldozed in a landfill. The survivors are worth a fortune.

Electronic Toys

Finally, think about the electronic toys you owned or wanted. Did you have a crystal set? Remco broadcast station? There were construction articles for early shooting games your dad could build with you if mom would let him. Did she?

Calling Dick Tracy. Calling Dick Tracy!How about a battery operated telephone or walkie talkies? Then there were infrared communicators, electronic accessories for model railroads, remote controlled airplanes and wrist radios that--well, weren't very good radios, and much more.

Calling Dick Tracy. Calling Dick Tracy!How about a battery operated telephone or walkie talkies? Then there were infrared communicators, electronic accessories for model railroads, remote controlled airplanes and wrist radios that--well, weren't very good radios, and much more.

Your childhood lives, at least on eBay. Perhaps it’s time to bring some of it home.

Collecting Related Items

Collecting, restoring and displaying pocket radios is fun, of course, but many of us enjoy owning a wider range of artifacts as vintage electronics magazines, test equipment, NOS components and, of course, electronic devices other than pocket radios. Let’s look at some examples.

Collecting, restoring and displaying pocket radios is fun, of course, but many of us enjoy owning a wider range of artifacts as vintage electronics magazines, test equipment, NOS components and, of course, electronic devices other than pocket radios. Let’s look at some examples.

Ephemera

If you Google the phrase “ephemera definition” you will get about two-dozen slightly contradictory hits. For me, the best summary of the general consensus seems to be “bits of throwaway paper of every day life (eg: advertising, ticket stubs, programs, some booklets and pamphlets),” and so on.

...items of collectible memorabilia, typically written or printed ones, that were originally expected to have only short-term usefulness or popularity.

Many definitions exclude books, but include catalogs, but for our purposes let’s include both catalogs and instruction manuals in our definition. Here are some examples of popular mid-century electronics-related paper collectibles.

Catalogs

High on any collector’s list ought to be a stash of vintage catalogs and flyers from retailers such as Allied, Heathkit, Lafayette, Olson Electronics, Poly Pak and so on. But if you stop there you are missing half the fun. Real ephemera hounds also round up manufacture’s catalogs, in-store handouts and so on.

Flipping through these musty pages can provide an amazing number of sense memories. Catalogs are like time machines. You will remember long-forgotten moments from your childhood, I promise. Flip through at least one catalog from the mid-fifties through the mid sixties and you will see what I mean.

Catalogs are also important research tools. They can help you date items in your collection, as well as look up battery cross-reference information, connector types and more.

Factory Announcements

Radio shops and other retailers were flooded with propaganda from manufacturers. Collecting product line sheets, price lists press releases and even personalized letters can be a great source of information and enjoyment.

Here too, these little scraps of paper help us gain perspective. It’s fascinating to compare the penciled-in prices on a radio shop’s marked-up “counter catalog” with the same shop’s factory price list. Which items sold below the recommended retail? Which ones went at a premium?

How valuable were radios to consumers? When you consider that the Federal minimum wage was $0.75 an hour in 1955 and only $1.25 a decade later, a $50.00 radio would have been a significant investment.

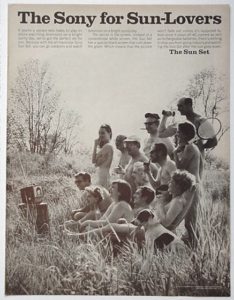

Magazines: Ads and Articles

Another wonderful source of enjoyment and information came to us through our mailboxes—electronics magazines. The big ones were, of course, Popular Electronics and Electronics Illustrated. If you were a hobbyist as a child I bet you flipped to Carl and Jerry the minute you picked up a new “Pop ‘Tronics.” Did you read Uncle Tom’s Corner in Electronics Illustrated? Was that guy irreverent, or what? Did the ads for trade schools get you thinking about a career in electronics? How many of those projects did you build, or want to build?

Another wonderful source of enjoyment and information came to us through our mailboxes—electronics magazines. The big ones were, of course, Popular Electronics and Electronics Illustrated. If you were a hobbyist as a child I bet you flipped to Carl and Jerry the minute you picked up a new “Pop ‘Tronics.” Did you read Uncle Tom’s Corner in Electronics Illustrated? Was that guy irreverent, or what? Did the ads for trade schools get you thinking about a career in electronics? How many of those projects did you build, or want to build?

Well, you can still build them today. Vintage electronics magazines are readily available and a real bargain for nostalgia buffs. Get yourself a handful and some vintage parts and dust off that soldering iron. You can’t be young again, but you can remember a lot about what it was like.

While you are at it, peek into some general “how-to’ magazines such as Popular Mechanics magazine and Popular Science also carried how-to projects, product reviews and fascinating technology-related articles and advertising. These are easy to find in local antique malls as well as online.

Many of the pop culture magazines including, but by no means limited to, Life, Look, Boy’s and Life are worth a look, if only for the advertising and cultural context they offer.

There is a thriving business devoted to the clipping and preserving of old magazine ads by the way. There are a number of online sources who will sell you an old Zenith or Toshiba ad framed, or at least preserved in an acid-free protective container. Expect to pay anywhere from a few dollars to more than $100.00, depending on an ad’s scarcity, condition and presentation. Google “vintage advertising” to get you started on your hunt.

There is a thriving business devoted to the clipping and preserving of old magazine ads by the way. There are a number of online sources who will sell you an old Zenith or Toshiba ad framed, or at least preserved in an acid-free protective container. Expect to pay anywhere from a few dollars to more than $100.00, depending on an ad’s scarcity, condition and presentation. Google “vintage advertising” to get you started on your hunt.

Service Documentation

Even if you don’t actually repair radios, you can learn quite a bit from service-related ephemera. Service documents from both manufacturers and technical publishers are definitely worth exploring.

Even if you don’t actually repair radios, you can learn quite a bit from service-related ephemera. Service documents from both manufacturers and technical publishers are definitely worth exploring.

Factory service documentation is often the most interesting, and most challenging to find. Some of the Japanese documents are absolutely stunning with photo-typeset text, wonderful art, and in many cases full color printing on glossy paper stock. These are collectible even if you don’t understand a word in them, (which can be the case if you are lucky enough to find them in their native language).

At the other end of the spectrum you will find factory documents that appear to be slapped together in an hour or two. Remember, this was a time before laser printers and scanners and PhotoShop, so many service documents were created on manual typewriters, and illustrated by cutting hand-drawn ink drawings with a razorblade and pasting them (sometimes haphazardly) onto cardboard for the lithographer to photograph.

Sams Photofacts are the next service document category. Howard W. Sams & Company, Inc. (an Indianapolis, Indiana publishing firm, which still exists today), worked with electronics manufacturers to create comprehensive, multi-page service documents for many popular electronic devices. They created documents for tube radios, televisions, audio products, Citizens Band radios, and when the time came transistor radios.

These were fold-out booklets with holes punched in them so that a technician could file them in three-ring binders. My recollection (from selling these to servicemen as a boy) is that you could not simply buy one Photofact. Instead, you purchased an envelope containing a dozen or more Photofacts in order to get the one you wanted. There was a subscription service as well, which saved you a trip to the parts store, and meant that new documents conveniently arrive in the mail.

Each individual Photofact document contained information about a particular model or series, or perhaps “chassis.” In the case of transistor radios you will typically find the following in a Photofact:

- Information about the manufacturer, and possibly the item’s distributor;

- The variations covered by the document (different model numbers for identical radios in different pastic colors etc.)

- the required power source and current consumption;

- alignment instructions;

- sometimes, but not always disassembly instructions;

- a schematic with test points and expected voltages marked;

- photos of the top and bottom of circuit boards with callouts locating the test points and components.

These documents usually came out after sets were on the market, but they sometimes pre-dated product releases. They often do not contain service updates or production changes, something that can both entertain and confuse today’s hobbyist, just as it must have confused folks hunched over the service bench “back in the day.”

The next logical progression was for Sams to publish books containing collections of Photofacts. In the case of transistor radios these collections were titled Servicing Transistor Radios and curiously abbreviated “TSM,” which I take to mean “Transistor Service Manuals.” I wonder why they were not called STRs?

At any rate, a typical TSM contained 50 or more Photofacts and an index to all the preceding TSMs. The first 50 TSM books more than cover the date range of interest to most boomer-aged collectors, and if you stopped at TSM Volume 35 you would probably still have a mighty useful collection.

TSM Volumes 1 through 6 contained a serialized article designed to bring tube technicians into the solid state age. It is titled Techniques in Servicing Transistor Circuits, and is worthwhile reading even today, particularly if you understand vacuum tube theory, as the majority of the intended readers did at time of publication.

This lengthy tutorial spans TSM Volumes 1-6 and was derived from articles printed in a Sams magazine called PF Reporter another interesting and valuable resource.

The first printing of TSM Volume 1 was in April 1958. Most of the early TSMs had multiple printings, which sometimes, but did not always contain updates and notes about production changes.

Every company needs a competitor, and H.W. Sams had a few. Perhaps the most useful to us was Supreme Publications, publisher of the Most-Often-Needed series. These were annual publications covering both tube and transistor radios. The coverage is considerably condensed compared to Photofacts and sometimes copies of factory-generated documentation not found in the Sams versions. There are also a few radios in the Most-Often-Needed series that you won’t find documented by Sams.

Service Aids are also wonderful collectibles. For example, consider this “PHILCOtrace automatic circuit evaluator from Philco, circa 1960. It contains printed templates that you place over the circuit board traces of a faulty set. The holes in the template let you use a test probe to compare your readings to the expected values, and to quickly trace signals through the set. How cool is that? Don’t you wish you had one for each of your radios?

Personal Notes, Receipts and Photos

Perhaps my favorite ephemera come from the original owners of vintage devices. These little slips of paper speak volumes. Examples include sales slips that tell us when and where a radio was purchased, at what price, and often, by whom.

Another wonderful find was a handwritten note to Heathkit from a frustrated builder and the lengthy the typewritten reply from Heath’s tech support staff telling him how to get his transistor radio kit working properly. (Try getting that kind of help from Dell, or just about anyone else today!)

Another great find was a hand-drawn schematic generated by the owner of a Regency TR-1. Was this guy a curious experimenter or a competitor?

And then there are childhood photos, or better yet childhood accompanying adult photos, showing someone regaining an important touchstone. Priceless!

Electronics Books

It’s remarkably easy to collect a nice library of vintage electronics books. These are generally inexpensive, plentiful and fun to read. You will obviously want to find topics of interest to you. I like the old construction and circuit books, typically 100-pages or shorter in length filled with circuits and construction diagrams. There are theory books, of course, engineering tomes and cross-reference guides.

Don’t limit yourself to English language books. Not everything happened in the States, you know. Here are a few examples of my favorite old books. Oh, and slide rules. You do have an amazing new slide rule right? It separates the men from the boys!

Signs and display cases

Merchandising items can be fun too. Radio makers provided dealers with fancy display cases, battery dispensers, posters, banners, wall clocks and other “point of purchase” propaganda.

Putting the right grouping of Motorola radios a proper case form the era can add a whole new level of authenticity to your collection. Even non-collectors love to look at vintage framed ads, banners and neon signs. “Oh, I remember those!” visitors will say.

These merchandising artifacts can be expensive, particularly if they are in excellent condition. They are also expensive to ship safely. A lot of what’s left out there is water damaged, nicked, chipped, or incomplete. Shop carefully, and ask plenty of questions.

What Do You Think?

Do you have tips and experiences to share? Questions? Suggested corrections or additions? Leave a comment below. I’ll review comments and post or incorporate the most useful ones. Your email address is required if you choose to comment, but it will not be shared.

I’ve worked in radio since 1979 but only starting collecting a couple of years ago. I collect the pocket and mini transistors from 50’s through the 80’s. I just love the look especially the radios from the 50’s and 60’s. I’m fascinated by traditional radio. The magic of transmitting a signal to one of these radios has given me a fun, life-long career. I am now considering learning to repair some of the radios I have found. Someone in the Facebook Transistor Radio group I’m in suggested your website to help me get started. It’s EXACTLY what I need. Thanks for making all this info and data available for those of us just getting started.